Hilltops and Headstones

The graveyard was divisive.

It sat directly outside our university Halls of Residence, in the oldest part of the city. Many students found it eerie. Distasteful. Downright terrifying: “what if they come IN my window?”. Some A & B Block residents even tried to swap rooms with those of us on the other side of the corridor (view: carrier bags hung out of windows keeping milk cold, and Type As playing Ultimate Frisbee) with varying degrees of success. One girl took up with a guy whose principle attraction appeared to be his F Block address (view: Seaton tower blocks, and Lidl).

The med student across the corridor from me, though, loved her deceased neighbours. “I find the view peaceful,” she’d say. “It’s kind of nice to know that none of this will really matter in the end.” By ‘this’ she meant, if I recall correctly, the pile of books on her desk, the rammed-full academic timetable putting my MA programme to shame, and probably the Invernesian stoner in room 105.

I still remember her words whenever I spend time in graveyards, which mystifyingly is something that seems to happen with increasing regularity as I get older. She was right. They are peaceful places.

I know this is not always the case. Death, while inevitable, is often a painful process for those in its vicinity, and if there is one common denominator in a graveyard, death is it. The sight of a headstone with too few days between the two dates will always hurt. Flowers, teddy bears and tragedy are always around the corner in a modern cemetery.

But the older places - those where you cannot be buried now save for being the fortunate progeny of distinguished forebears with morbid foresight, or those where the lairs remain the preserve of ancient churchmen and their lackeys - these are peaceful.

We visited the Glasgow Necropolis yesterday. My husband has a Weekend Walks book which details walking routes around the city. He’s more of a fan of Outside and of Exercise than I am, but I like spending time with my family so we picked the next walk from the list and took the train into town.

Inspired by the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, Victorian weegies began to warm to the idea of their bones resting in a location other than the grounds of the local parish church, and in the 1830s the Necropolis was opened. People being what they are, competitive memorialisation ramped up and we are rewarded two centuries later with a fascinating place to spend a blowy January afternoon in between Greggs visits for our perpetually-ravenous teen.

Not every grave is marked by a headstone, and of those that remain some are weathered into lichen-crusted illegibility. But many have stood firm in the face of decades of dreich Glasgow weather, and others clearly benefit from regular restoration and maintenance work. From the simplest of stone slabs to the bigger-than-my-first-flat mausoleums, each one tells a story of the ones who rest beneath.

Glasgow Necropolis. Photo by author

Some don’t even have residents below. “Buried at sea”. “Interred by the battlefield”. These are just as melancholic to me; knowing someone missed them enough to want a place close by to visit and remember.

Many occupants seem defined mostly by their occupation.

Chartered Accountant.

Ship Owner.

Bank Manager.

Merchant.

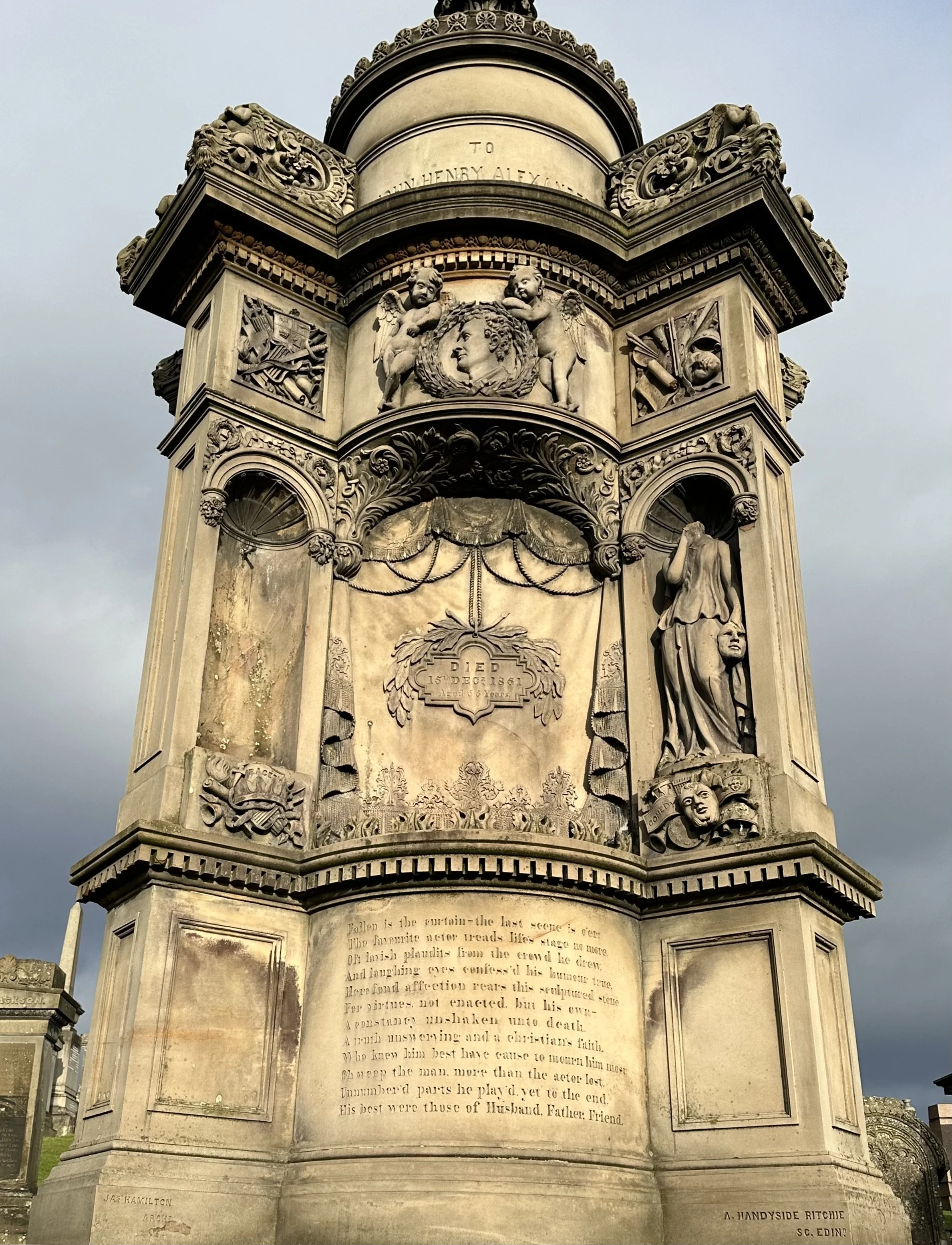

Others, though, celebrate their relationships - such as this memorial to John Henry Alexander, actor and theatre owner:

Memorial to John Henry Alexander. Photo by author

“Oh weep the man, more than the actor lost,

Unnumbered parts he play’d, yet to the end,

His best were those of Husband, Father, Friend.”

The views from the Necropolis peak are something else. The city sprawls around you, from the Cathedral and hospital below, to the Campsie hills in the north, and the Cathkin Braes and Whitelee windfarm to the south. Exposed, high on this city-centre hill, the grave markers gather in amicable groups, communal defence against buffeting gusts.

View over the south of Glasgow. Photo by author

My daughter, effervescent and inexhaustible, leapt up the steps of each mausoleum, calling greetings to its inhabitants. My son, contemplative and curious, counted and compared material durability. He took pictures of the original intended entrance to the graveyard, and considered it an excellent setting for a story which would involve the 5 Beasts of Glasgow, ready to be unleashed. No, Rick Riordan, you can’t have that idea.

Original planned entrance to Necropolis, carved from red sandstone. Photo by author

Spending Saturday afternoon in a city of the dead might not be for everyone, and I wouldn’t want to do it too regularly myself. But as a way to remind ourselves of our place in a spinning constellation of history and the ancestors, it's hard to beat. And buying Greggs sausage rolls, pizza slices and muffins for the train ride home seemed an excellent way to celebrate the contrasts of life.

© Fiona McDerment, 2024. All rights reserved.

Article originally published via Medium - visit my profile here